|

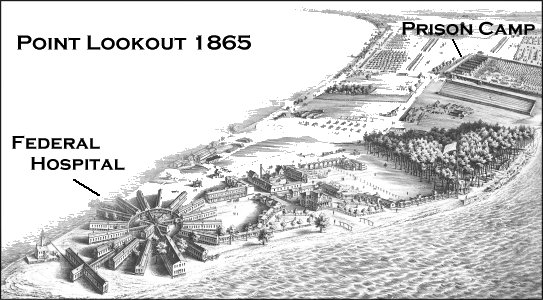

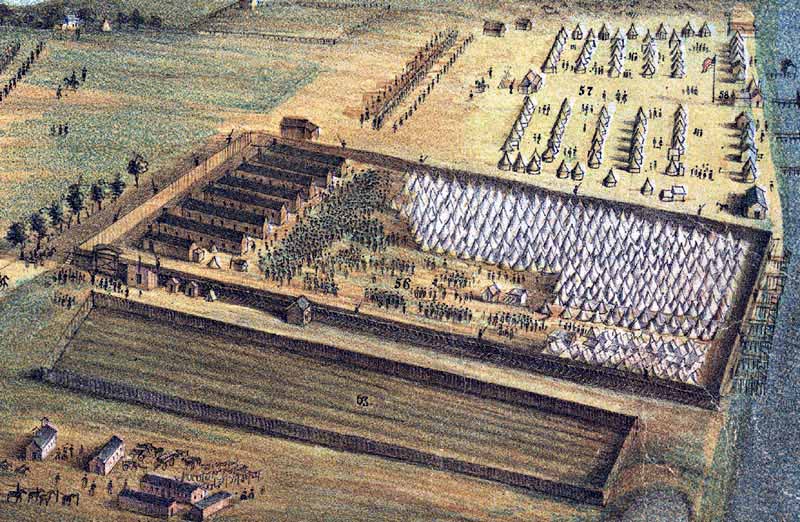

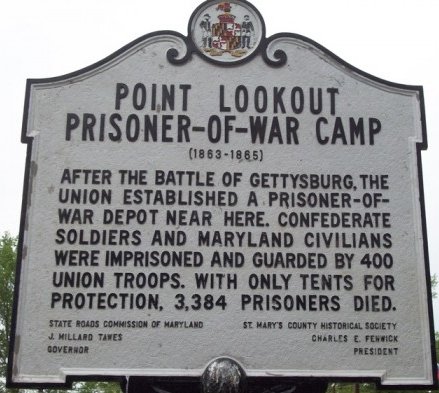

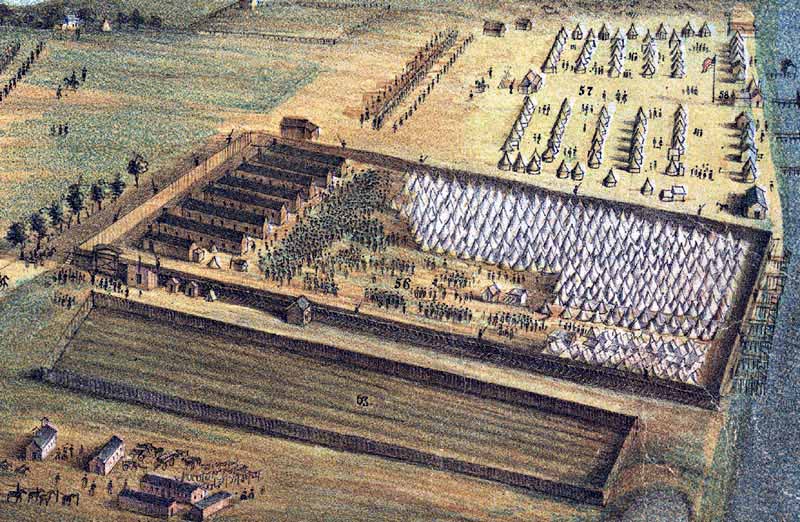

As the Civil War progressed into its up scaled battles, feeding more men into the teeth of hell, both governments sought more real estate to establish their prisoners of war. A federal prison camp for Confederates was built on Point Lookout, Maryland, at the extreme tip of St. Mary's County, on the barren peninsula where the Potomac River joins Chesapeake Bay. The camp was convenient to the battlefields in the East and therefore became the largest Union prison. The camp was established after the Battle of Gettysburg to incarcerate Confederate prisoners. The camp was in operation two years, July, 1863-June, 1865.

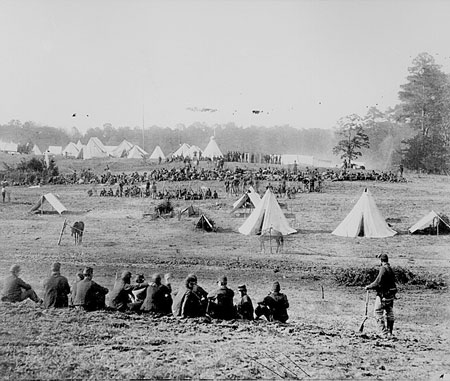

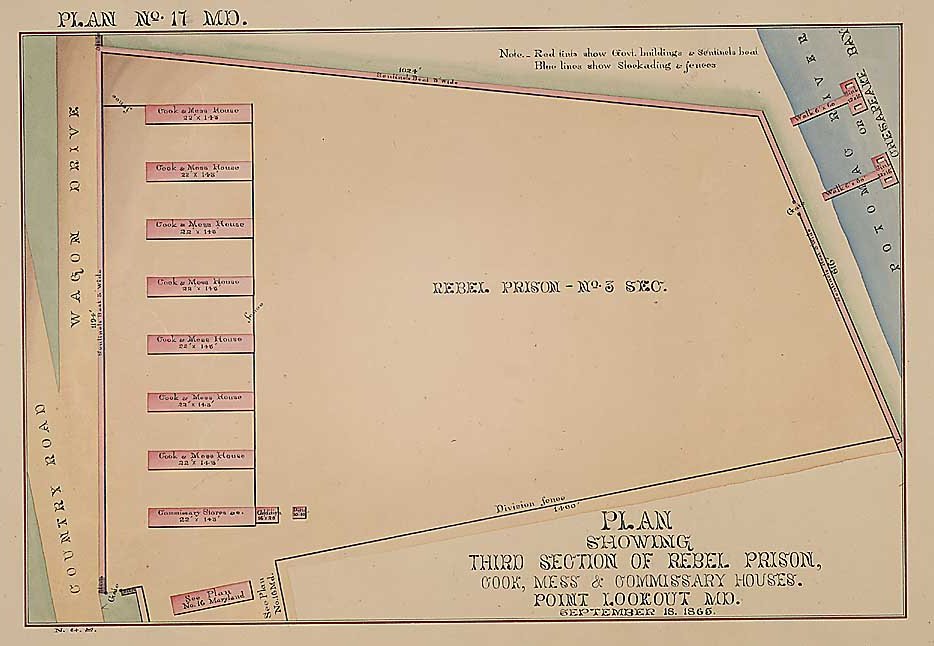

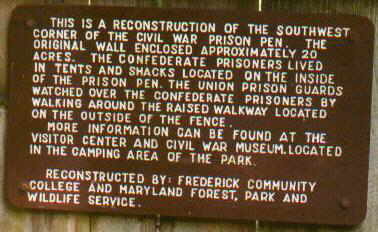

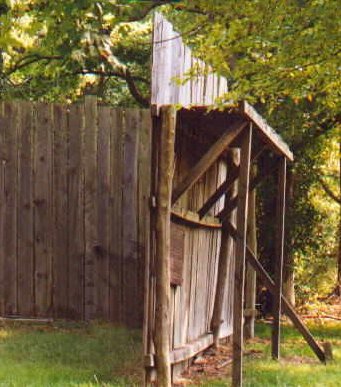

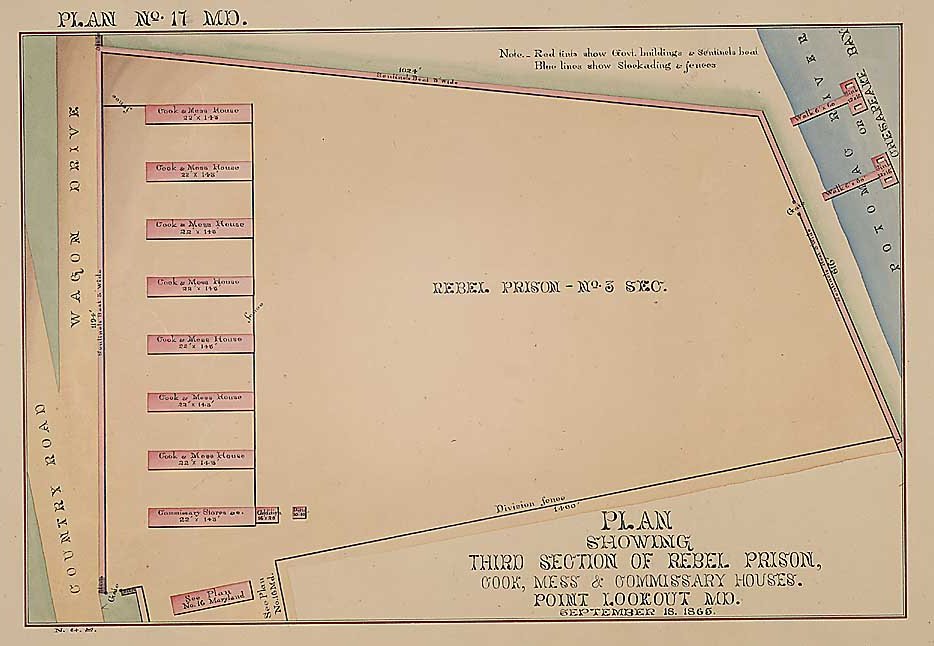

The prison consisted of "two enclosures of flat sand, one about thirty and the other about ten acres, each surrounded by a fence fifteen feet high, without tree or shrub. The camp was only about 5' above sea level.No barracks were ever built. The Confederate soldiers were given tents to sleep in until overcrowding became so bad, there were not even enough tents to go around. ated in Saint Mary's County, Maryland on the southern tip of the peninsula was deemed the largest and worst Northern POW camp. Point Lookout was constructed of fourteen foot high wooden walls. These walls surrounded an area of about 40 acres. A walkway surrounded the top of the walls where negro guards walked day and night. It is reported the guards were brutal in their treatment of prisoners.

|

|

Camp Map ~ Click for larger image ~

|

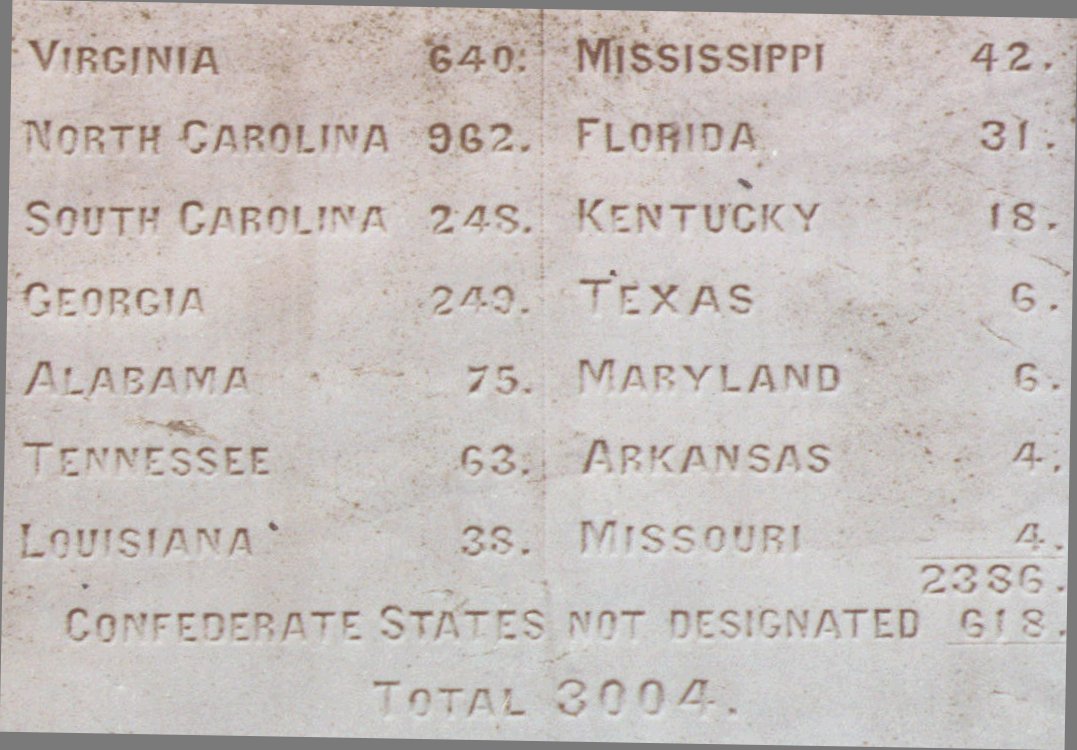

Because of the topography, drainage was poor, and the area was subject to extreme heat in the summer and cold in the winter. This exacerbated the problems created by inadequate food, clothing, fuel, housing, and medical care. As a result, approximately 3,000 prisoners died there over 22 months.

It is estimated that a total of 52,264 (WOR) prisoners, both military and civilian, were held prisoner there. Although it was designed for 10,000 prisoners, during most of its existence it held 12,600 to 20,000 inmates.Approximately 50,000 Confederate enlisted men were contained within the walls of Point Lookout Prison Camp during it's operation 1863-1865. Prison capacity was 10,000 but at any given time, there would be between 12,000 and 20,000 soldiers incarcerated there.

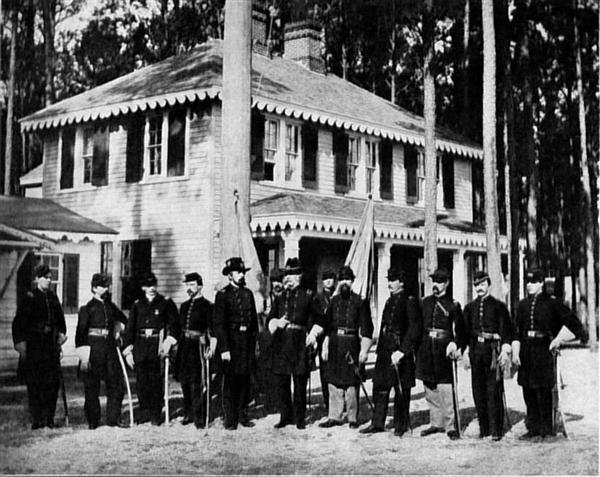

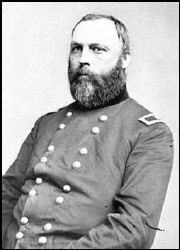

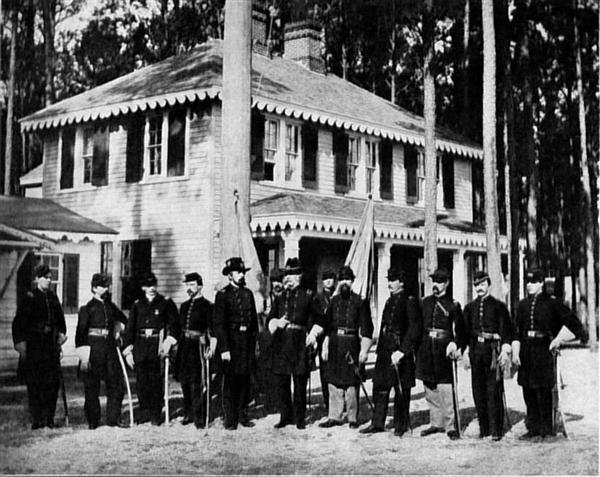

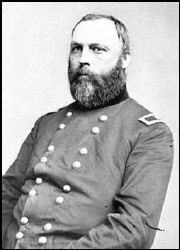

The camp's Provost Marshall was Major A. G. Brady assisted by Major Gen. Benjamin Butler.

|

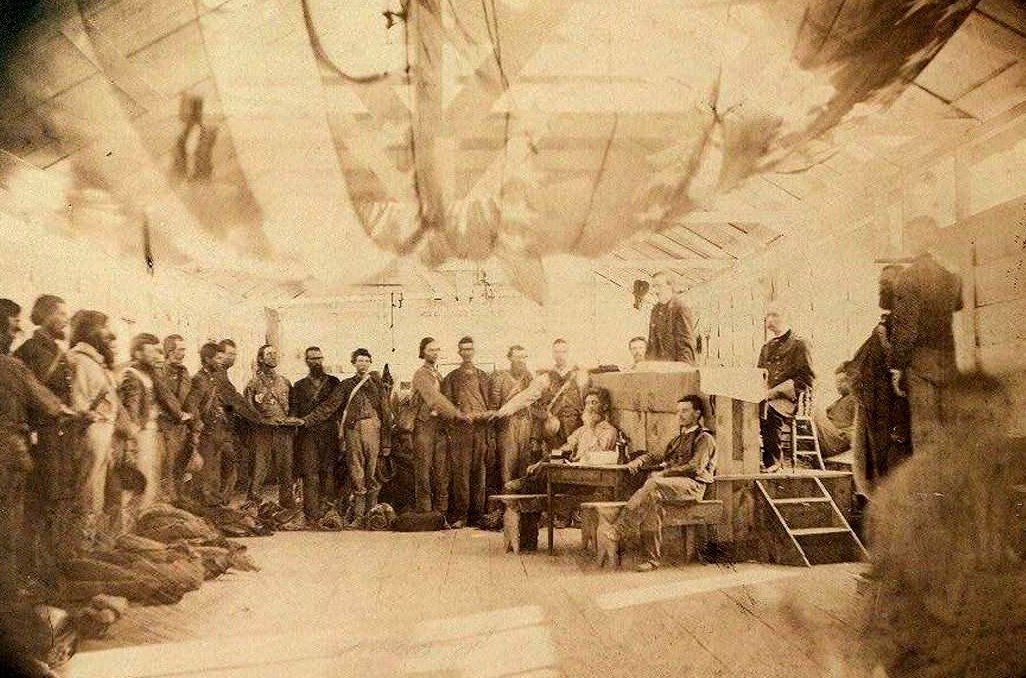

Major Brady & Staff |

|

Benjamin Butler |

|

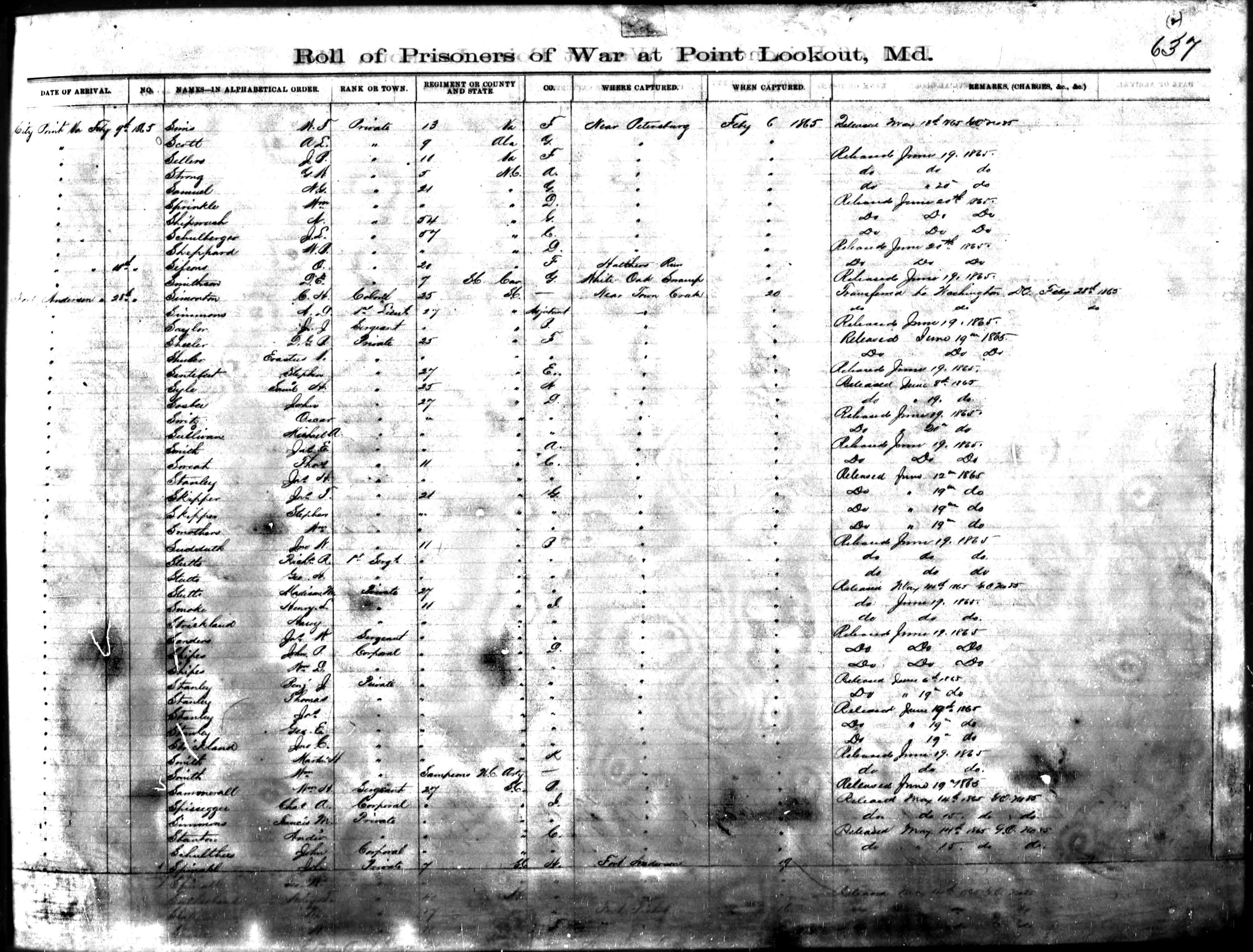

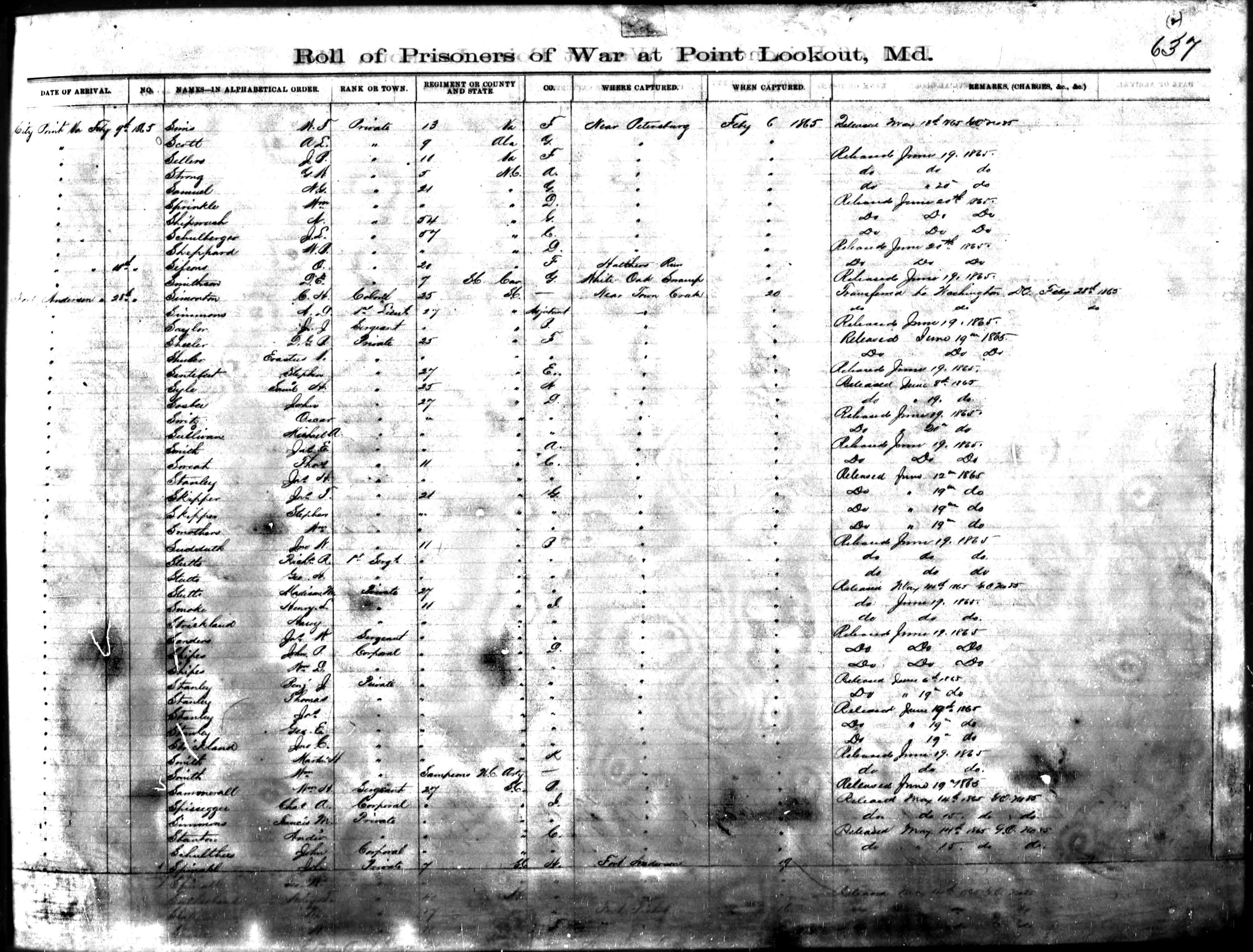

Roll of Prisoners |

|

The Chesapeake Bay detained the inmates on their side of the stockade, while the mouth of the Potomac River kept any working parties from ideas of escaping into Virginia. This setup made life during the winter brutal on the soldiers held there. Housed in shelter halves with firewood scarce and blankets in low quantity, it proved to be a cold miserable place to sit out the war.

The prisoners' ordeal began the minute they were placed on that unhealthy spit of land. They were forced to discard anything bearing the initials "U.S.," which for almost all Confederates meant more than half of their belongings. Men were crowded into drafty tents and allowed only one blanket regardless of the season. Firewood and the essentials for health and comfort were scarce. Confederate Sergeant Charles T. Loehr, captured on April 1, 1865, at the battle of Five Forks, received a rude awakening his first night at the camp. He was one of forty men placed in a tent designed for sixteen. Six or seven of the forty had died by morning, including the two on either side of Loehr.

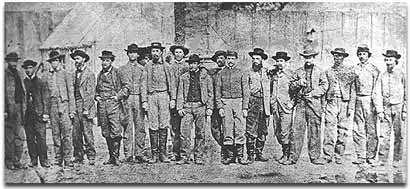

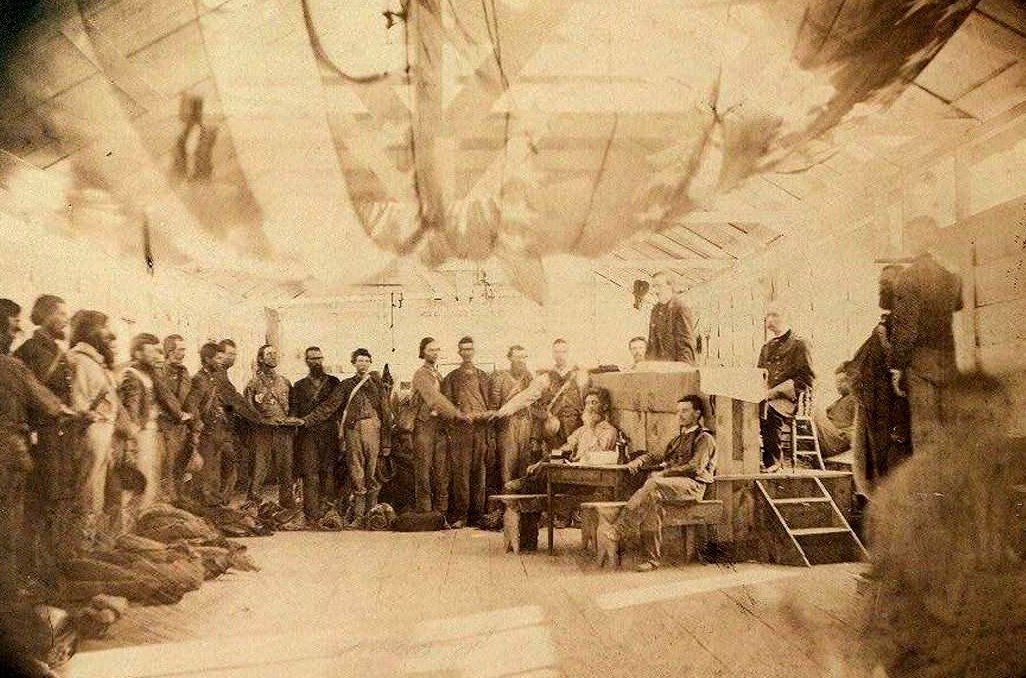

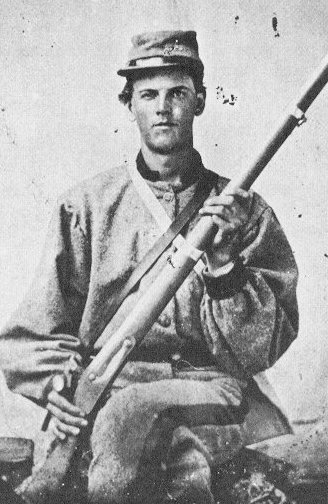

Confederate Prisoners

Federal authorities refused to permit Marylanders to aid the inmates with the bare necessities of life, and thousands of prisoners died for lack of food, medical care, or proper sanitary conditions. Loehr wrote that his captors were "negroes of the worst sort and very brutal; when the prisoners were driven out of their tents at night by diarrhea, the guards would make them carry them on their back; they were quick-stepped about the grounds, forced to kneel and pray for Abe Lincoln, etc.!" There was a "dead line" ditch some fifteen feet from the fence and any prisoner who approached it was fired upon. Confederate Sergeant Major of the Camp, P. Thoroughgood, reported that the "conduct and conversation of the colored men evidence that there is a sort of rivalry among them to distinguish themselves by shooting some of us." He wrote that the "one who does so gains an eclaim which the others envy; and animated frequently by vindictive feelings, they make pretexts to vent them."

The man responsible for these atrocities was Provost Marshall (Major) A.G. Brady, who, as it turned out, personally made in excess of $1,000,000 during his time as camp commander. The mortality rate at Point Lookout was greater than that of the Confederate prison at Andersonville, Georgia. Even more damning is that the fatalities at Point Lookout were due to unnecessary neglect, while those at Andersonville were due to a real want in the Confederacy as a whole. The official number of Confederate dead at Point Lookout was 3,384, but other accounts suggest that many more perished. Sergeant Loehr wrote that it was "not unusual to hear of 60-65 deaths per day and `it is said that 8,600 Confederate dead were buried near [the] prison pen.'" ...Prof. Bart Talbert, University of Salisbury, MD

In mid July of 1863, plans were in motion to establish a hospital prison at the tip of St. Mary's County and with the assistance of the Army's Surgeon General, Brigadier General William Alexander Hammond, provisions were made to render medical attention to those incarcerated there.

|

Wm. A. Hammond |

. |

Gillman Marston |

|

War Department General Order 226 assigned Brigadier General Gillman Marston to the newly established Saint Mary's County District to be headquartered at Point Lookout. With an established stockade and grounds to provide, the southern tip of St. Mary's began receiving its first shipment of prisoners from Fort McHenry as well as those in and around Washington City.

The hospital establishment itself was arranged as that of the spokes from a wagon wheel having fifteen separate wards, housing nearly fourteen hundred beds overall, with seventy to each ward. In addition to looking after the combat wounded, cases of typhoid fever, diarrhea and pneumonia were monitored and treated with a fully trained medical staff.

During the summer of 1864, the liberation of Confederate Soldiers residing there became an addendum to the Maryland Invasion of Major General Jubal Early. A blunder in command and control assigned Brigadier General Bradley Tyler Johnson to that task. While Early was floundering about Frederick, Maryland seeking routes and a ford across the Monocacy River, his only native to the area rode off on his impossible mission, finding the hospital prison impractical to carry.

Last Confederate Prisoners

During the summer following the surrender of all Confederate Forces, the last of the prisoners of Point Lookout were released, and on July 13, 1865 the Department of Washington issued Special Orders 168 discontinuing Point Lookout as a garrisoned post. The last of the federal troops moved on and the two year legacy of the Federal Hospital Prison at Point Lookout would quietly pass into the memory of what we call history.

|

|

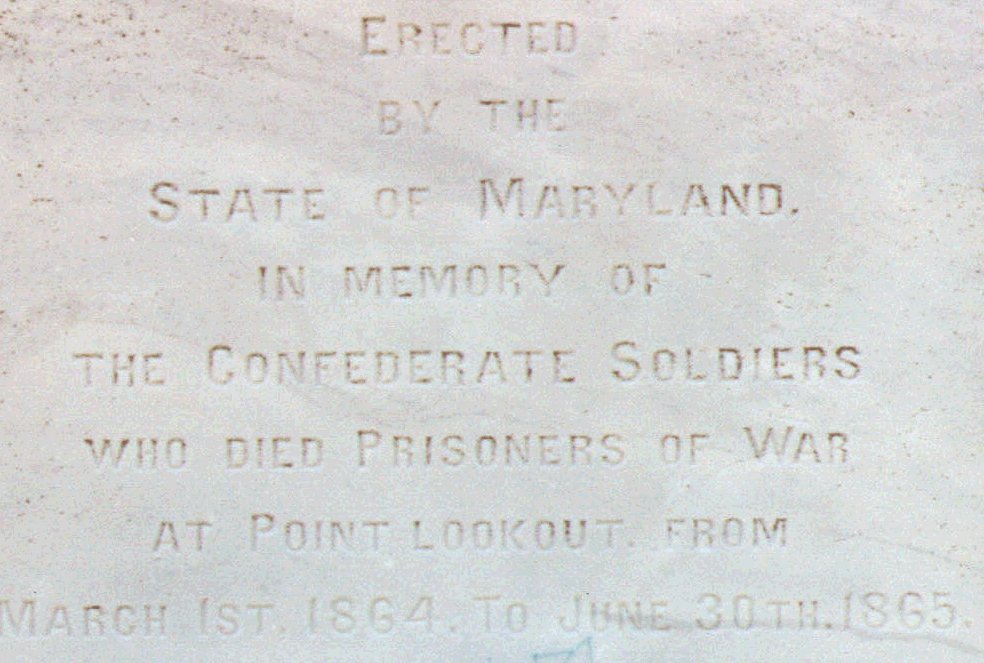

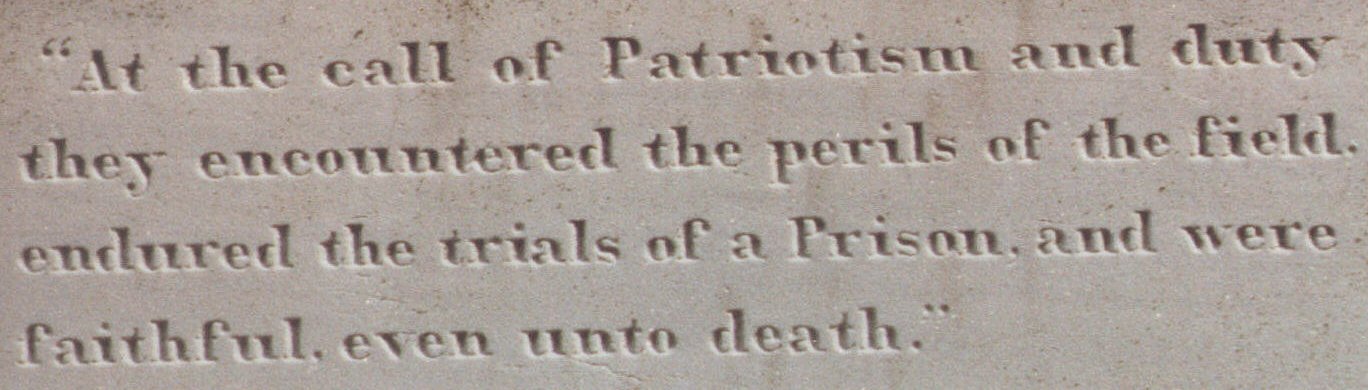

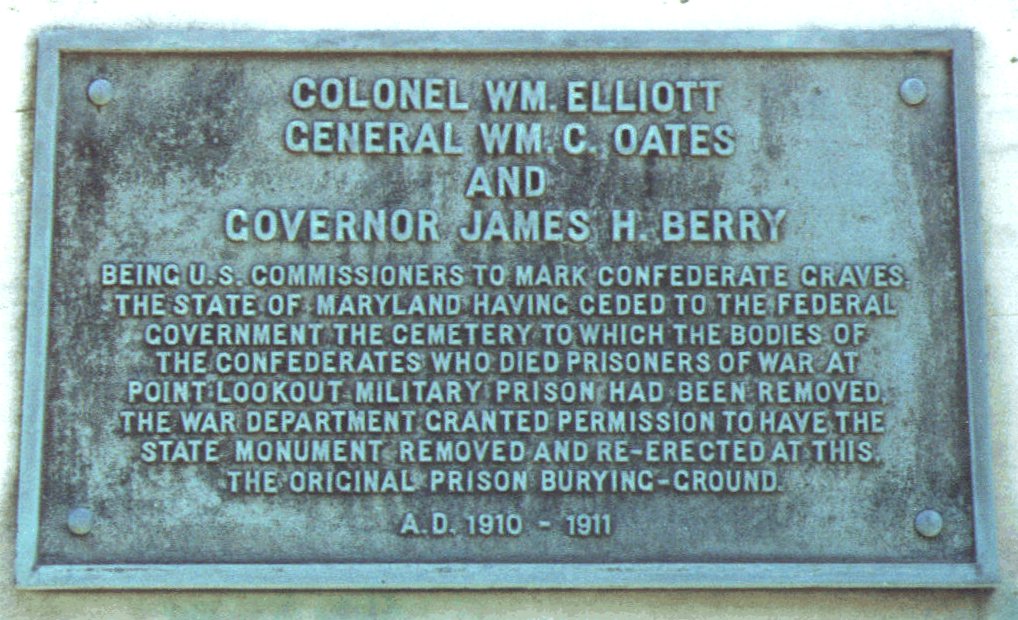

Today there are monuments erected to the men who died while held at Point Lookout.

A common marker contains an alphabetized list of those who died. The marker was erected by the State of Maryland in the 1930s.

Over the years much of the Point Lookout site and grave yards were lost to the waters and sands of the bay. The grave sites were move several times after 1866. The present cemetery site is Scotland. There are two monuments at Scotland in memory of the Confederate dead, one by the state of Maryland and the other by the Federal Government. The Maryland monument was moved to its present site in the cemetary at Scotland in 1938. The State of Maryland made an effort to reduce further loss by lining the shore with large boulders in later years.

|

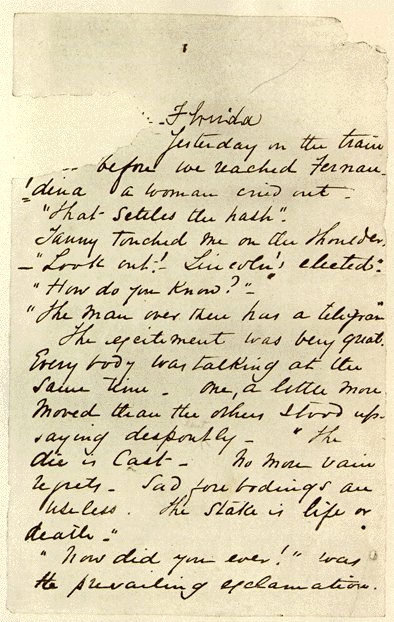

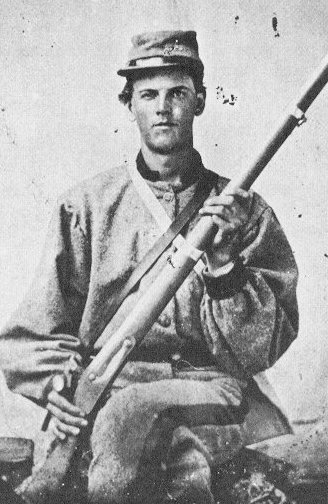

Two invaluable sources describing life in the camp are the diaries of Bartlett Yancey Malone and Charles Warren Hutt. Here are the detailed day by day happenings in the camp recorded as the events happened with no time lapse to dim or soften memory. These men were veteran campaigners, used to the hardships of war including slim rations and extremes of heat and cold so they recorded life in the camp simply as they experienced it, without exaggeration and with little rancor."

Sergeant B. Y. Malone

Co. H. 6th

No. Car. Infantry |

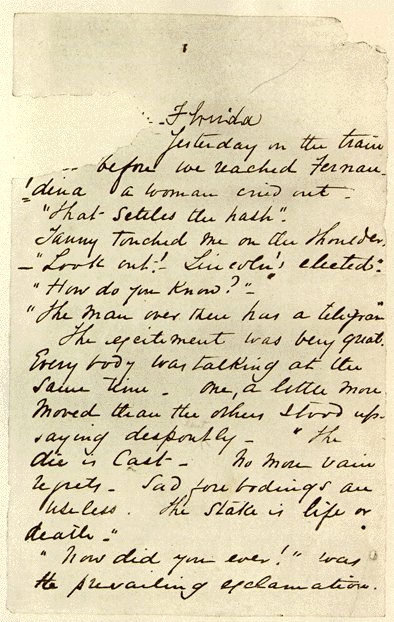

Diary Page

.

Read Malone's Diary

|

Private C. W. Hutt

Co K 40th

Virginia Vol. Infantry |

HOME

What's New -

Ancestors -

News Letter -

Photo Quiz -

Education -

Guest Book

School Day -

Join SCV -

Chaplain -

Photo Gallery -

Links -

Calendar

|

![]()