| Back |

The Carolinas Campaign

The Battle of Bentonville

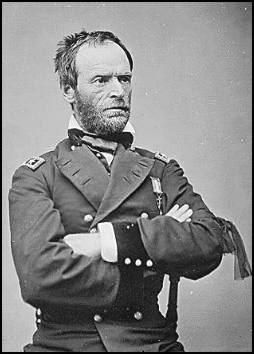

Sherman |

Sherman' March |

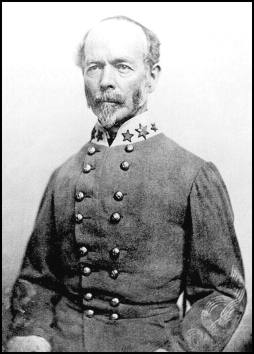

Johnston |

The Crisis of the Campaign

"I think it probable that Joe Johnston will try to prevent our getting Goldsborough." William T. Sherman to Gen. O. O. Howard, commanding the Federal Right Wing, March 18, 1865.

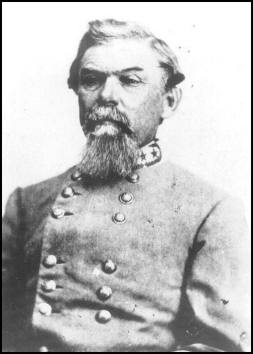

On March 16, 1865, as the Battle of Averasboro was being fought, Johnston appointed Lt. Gen. A. P. Stewart as commander of the Army of Tennessee remnants, which were still arriving at Smithfield. The Confederate troop concentration was going well, if slowly, and late that night Johnston queried Hardee: "Please give me all the information you have . . . in regard to [the enemy's] movements, in order that we may regulate our own accordingly." Johnston was eager to learn the direction of march of the Federal Left Wing column. From his headquarters at Smithfield, the Confederate commander was slowly drawing his forces together for a more substantial attempt to arrest Sherman's progress through North Carolina. Smithfield--situated roughly midway between Raleigh and Goldsboro, with a rail link to both towns--was an ideal base for Confederate operations. From here Johnston could move to the west to block an advance on Raleigh, or to the east to bar the way to Goldsboro.

Stewart

Hardee

Taliaferro

Hardee's stand at Averasboro had provided the inexperienced troops of Taliaferro's Division a chance to gain some combat experience. But more importantly it delayed the advance of Sherman's Left Wing for one day, buying precious time for Johnston's gathering forces.

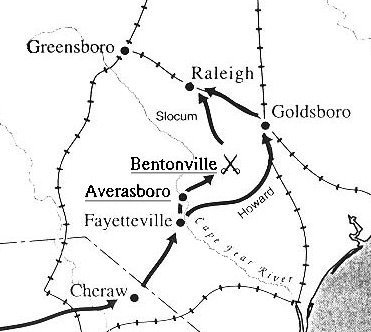

On the morning of March 17, Kilpatrick's cavalry and Gen. William T. Ward's XX Corps division followed the retreating Hardee as far as Averasboro. Sherman hoped to mislead the Confederates into thinking his army was marching on Raleigh. Meanwhile, the main body of the Left Wing turned east toward Goldsboro. As the Left Wing advanced, Gen. Wade Hampton fell back with Col. George G. Dibrell's troopers to Willis Cole's house on the Goldsboro Road, about two miles south of the tiny hamlet of Bentonville. That evening Hampton informed Hardee: "I think that the enemy is moving on Goldsborough . . . I will keep [in] between him and Smithfield and Goldshorough, until the very last moment."

Killpatrick

Dibrell

Hampton

Reports from the field were not prompt in reaching Johnston at Smithfield, and he began to worry that events were unfolding too slowly. He continued to press his subordinates for information. At 7 p.m. he warned Hardee: "Something must be done tomorrow morning, and yet I have no satisfactory information as to the enemy's movements. Can you give me any certain information of the position of the force you engaged yesterday [at Averasboro]? Send it immediately by a trusted and well mounted courier, to come all the way rapidly." Having learned that the Federals were moving east, Johnston turned his attention to Hampton at Cole's house: "Please send me . . . all the information you have of the movement and position of the enemy, the number of their columns, their location and distance apart, and distance from Goldsborough, and give me your opinion whether it is practicable to reach them from Smithfield on the south side of the [Neuse] river before they reach Goldsborough." To facilitate deployment, "Old Joe" ordered Bragg and Stewart to be ready to move out at dawn the next morning.

Hampton finally supplied Johnston with some encouraging news. In reply to the general's plea for information, Hampton stated that his present position at the Cole plantation would be an excellent site at which to block the advance of Sherman's Left Wing. The Federals were still a day's march away from Cole's, and were sufficiently separated from the Right Wing. Smithfield lay some twenty miles north of Hampton's position, and he assured Johnston that his cavalry would hold Sherman's advance in check while Johnston's forces gathered at the chosen site. With this news the Confederate commander decided the time for action had come, and hastily prepared to unite his forces with Hampton's below Smithfield. At 6:45 on the morning of March 18, Johnston's adjutant penned a dispatch to Hardee, whose corps was encamped at Elevation, midway between Averasboro and Smithfield: "[P]ut your command in motion for Bentonville by the shortest route . . . . The sheriff of this county represents that there is a road leading from a point two miles this side of Elevation and striking the Averasborough and Goldsborough road a little to the west of Bentonville."

Unfortunately for the Confederates, Johnston's maps of the region would prove sorely inaccurate, placing Hardee closer to Bentonville than he actually was--and more importantly, exaggerating the distance between Sherman's separated columns. These discrepancies would delay Hardee significantly. At 7:40 a.m. Johnston himself notified Hampton: "We will go to the place at which your dispatch was written [Cole's plantation]. The scheme mentioned in my note, which you pronounce practicable, will be attempted. Send all the information you can bearing upon it."

Sherman's Confidence

Until now Sherman had remained wary of the intentions of his adversary: "I think it probable that Joe Johnston will try to prevent our getting Goldsborough," he wrote to Right Wing commander Oliver O. Howard on March 18. Sherman's maps were no better than Johnston's. "Our map is evidently faulty," he complained to Howard, "[and] I fear Slocum [commanding the Left Wing] will be jammed with all his trains in a narrow space; but at the same time I don't want to push you off too far till this flank is better covered by the Neuse."

But soon Gen. Judson Kilpatrick told Sherman what he wanted to hear, reporting that the enemy was retiring on Smithfield. Word also came in that Joseph Wheeler's Confederate cavalry had burned the bridge over Mill Creek on the Smithfield-Clinton Road [in the vicinity of present-day U.S. 701]. Sherman's map incorrectly indicated this road as the only approach route available to Johnston from Smithfield. (The map omitted Johnston's actual approach route, which met the Goldsboro Road two miles south of Bentonville near Cole's plantation.) It suddenly looked as though Johnston was going to defend Raleigh, instead of Goldsboro. Sherman's confidence was building, and he felt that the Left Wing would easily reach Cox's Bridge on the Neuse River by the next afternoon. From there it would be a 12-mile march to Goldsboro.

On March 18 the Left Wing, traveling on the Goldsboro Road, advanced as far as the intersection of the Smithfield-Clinton roads. The head of the Right Wing's XV Corps was some two miles to the south at Blackman Lee's Store, while the XVII Corps was six miles further south and east at Troublefield's Store. Sherman's army, more compact than it had ever been thus far on the grand march, was within 25 miles of Goldsboro.

As the Left Wing column drew near, Hampton deployed Dibrell's troopers and William Earle's South Carolina battery in a defensive line at the Reddick Morris farm, just west of Cole's plantation. At 2:30 p.m. Hampton sent word to Johnston: "I can hold [Slocum] here for several hours more, and I do not think his advance will get beyond this point tonight." At dusk the Confederate cavalry force was pressed hard by a 90-man party of mounted foragers from Morgan's XIV Corps division, but the thin line of Southern troopers held.

Hampton had successfully defended the ground chosen for the coming fight. As the Southern cavalry leader clung to his position on the Morris Farm, Johnston's infantry was hard on the march from Smithfield, and Bragg and Stewart would reach the village of Bentonville during the evening of March 18.

The Battle of Bentonville

March 19 - 21, 1865

Confederate G. Joseph E. Johnston had managed to accumulate 21,000 men and at last was ready to confront Union Gen. William T. Sherman's forces as they marched through North Carolina. His plan, a rare offensive movement for Johnston, was to attack Gen. Henry W. Slocum's two-corps column, separated by 10 miles from the rest of Sherman's forces.

On the morning of March 19, 1865, Slocum's column clashed with Confederate cavalry just south of Bentonville. The Union troops pushed back the Southern horsemen until they found themselves under attack by Rebel infantry. Slocum quickly consolidated his troops, called for reinforcements, and managed to beat off Johnston's all day attacks with hard fighting. After dark, Johnston pulled his men back to a good defensive position.

There was little fighting on March 20. Sherman hastened his left column, commanded by Gen. Oliver O. Howard, to Slocum's aid. Johnston needed time to move his wounded to safety, and was content to hold his ground. Even with a three-to-one superiority in numbers and the Rebel force surrounded on three sides, Sherman was also hesitant to press the attack. He did not realize the odds were in his favor and he, too, had a large number of wounded.

The next day Sherman's men attacked the Rebel left flank. They were repulsed and the lines remained static until night, when Johnston pulled back toward Smithfield, having lost 912 killed and 1,694 wounded. Sherman's losses were 478 killed and 1,168 wounded.

Johnston's attack on Sherman was well planned and executed but he had too few men to carry it out. He wrote Gen. Robert E. Lee, "Sherman's course can not be altered by the small force I have. I can do no more than annoy him."

Fascinating Fact: On the morning of March 21, Confederate Gen. William J. Hardee, after months of pestering, finally gave in to his 16 year old son, Willie, and allowed him to join the 8th Texas Cavalry. A few hours later, the general came upon litter-bearers moving to the rear carrying Willie, mortally wounded in his first charge in the Battle of Bentonville.

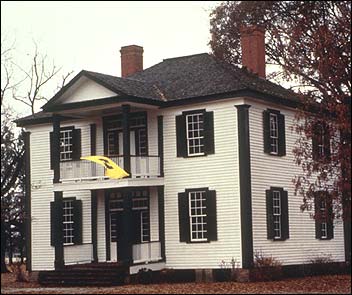

Harper House, (Visit Inside ~ Pictures)

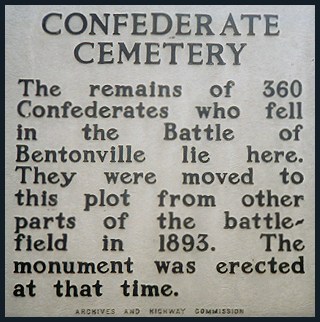

Historical Marker

A William Waud sketch of action at Bentonville, N.C.

March 21, 1865

HOME

About SCV -

Join SCV -

Legionary -

Co. News -

B.F.C. -

Member Services -

Education

B.F.C Site -

Ancestors -

Memorials -

Links -

Photo Gallery -

Guest Book -

Site Index